Geopolitics of the U.S. strategy in Central Asia

Geopolitical Report 2785-2598 Volume 13 Issue 9

Author: Silvia Boltuc

After the troop’s withdrawal from Afghanistan, the United States are expected to redefine their position in Central Asia to contrast the Kremlin’s Eurasian Economic Union and Collective Security Treaty Organisation, Beijing’s Belt and Road Initiative and Shanghai Cooperation Organisation and the Iranian regional strategy.

At the beginning of the century, the new Great Game focused on the Caspian energy reserves as an alternative to the Persian Gulf, which still holds two-thirds of the world’s oil reserves. The U.S. Energy Information Administration estimated that there could have been 33 billion barrels of oil reserves and about 232 trillion cubic feet of natural gas in the Caspian area. Contrary to initial expectations, the Middle East remains the wealthiest area in energy resources. Still, as Lutz Kleveman underlined in his book The New Great Game, the Caspian has become so important in the United States effort to wean itself off its dependence on the Arab-dominated OPEC cartel, which, since the oil crisis in 1973, has used its near-monopoly position as a pawn and leverage against industrialised countries.

On the other hand, the regional instability and the impossibility of securing the structures, as well as the issues related to the areas of competence, have had the effect of dissuading part of foreign actors from investing in the area, given the difficulty that would exist in the mining process and in ensuring the transport logistics chain.

The September 11th, 2001 terror attacks and the U.S. campaign in Afghanistan have pushed central Asia to the forefront of world attention after 70 years of isolation during Soviet rule.

During the last two decades, due to the U.S. involvement in the rebuilding of the Afghan nation and its fight against terrorism, Washington has hugely invested in Central Asia, particularly in training troops and leasing military bases in countries such as Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan, and the extraction of precious stones and metals.

Being part of the Soviet Union, although it did not increase the wealth of the Central Asian states, nevertheless allowed those countries to receive the services and assistance necessary for their survival. Following its collapse, except for the oligarchs of the energy industry, countries have experienced a sharp deterioration in their living conditions. Consequently, they enthusiastically welcomed the presence of the United States and other Western countries, believing that this would have driven the region’s development.

The United States’ situation in the Central Asian republics today is very different. The changes that Central Asian states expected with the advent of capitalism and democratic values have been small so that today some states are once again looking to Russia as an element of security and economic stability. Russia is basing its media strategy on this rhetoric, using soft power to cement its consensus in the area.

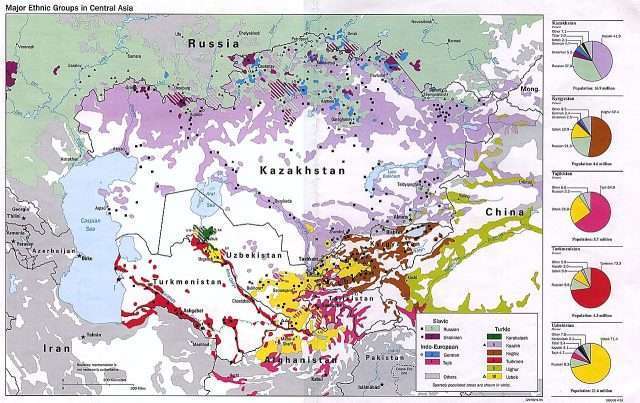

Ethnic Russians make up a large percentage of the Central Asian population, and therefore, being the Russian language widely spoken throughout the region, the Russian media is a significant source of news for a large part of the population. Russian social networks such as Odnoklassniki and Vkontakte are also quite popular in Central Asia.

In addition, through Russian-led organisations such as the Collective Security Treaty Organisation (CSTO), which provides cooperation on military and security fields, the Eurasian Economic Union (EAEU), which encourages the free movement of goods and services, and the Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS), which enhance cooperation and dialogue between the ex-Soviet Republics, Russia tries to be the leading actor in the region. According to the Foreign Ministry, the Kremlin has invested 20 billion dollars in Central Asia.

Among the many agreements and cooperation fields between Moscow and the Central Asian republics, particularly important are the links with Kazakhstan, the two military bases in Tajikistan, which, thanks to an agreement signed in 2012, will guarantee the Russian military presence in the country till 2042, and an airbase in Kyrgyzstan.

Washington’s strategy in Central Asia since 9/11

Following 9/11, Washington negotiated with Central Asian states to locate its troops in the region. Uzbekistan provided an airbase at Khanabad airport (in exchange, Tashkent received 125 million dollars to purchase weapons for the fight against terrorism) and at Kyrgyzstan, at Manas International Airport. The following year, the United States invited Uzbekistan to sign the Strategic Partnership Agreement for Security Cooperation.

The presence of U.S. troops in Central Asia was perceived as a security threat by Russia and China. By lobbying through the SCO, the two countries achieved the closure of the Khanabad air base in 2005. The same strategy was used through the CSTO to force Kyrgyzstan, which has become a member of the EAEU, to close the U.S. airbase of Manas and withdraw from a 22-year cooperation agreement with the United States.

Nonetheless, the United States has adopted alternative strategies to strengthen its regional presence, for example, through significant investments and regional cooperation formats.

Washington signed the Development of Trade and Investment Relations Agreement with Uzbekistan. In 2019, the U.S. foreign direct investment spent 38 million dollars in Kyrgyzstan, 43 million in Tajikistan, 40 million in Turkmenistan, 82 million in Uzbekistan and 36 billion in Kazakhstan.

Furthermore, the United States initiated an annual bilateral consultation process with Tajikistan and Strategic Partnership Dialogue with Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan to enhance cooperation. In cooperation with the Central Asian Economic Community, Washington hosted meetings involving Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, and Uzbekistan that helped reach cooperative agreements on energy and water. In 2005 they created the C5+1 format involving the Republic of Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, and Uzbekistan.

The platform was created to enhance regional dialogue, cooperation, and partnership among the participating countries and has contributed to increasing economic and energy connectivity and trade, mitigating environmental and health challenges, jointly addressing security threats, and advocating for the full participation of women in all aspects of the political, economic, and social life of member countries.

In 2011, the United States also launched the project of a New Silk Road (NSR), linking India, Pakistan, Afghanistan and Central Asia, which in the words of Hillary Clinton, former U.S. Secretary of State, would have been a network of economic and transit links that would unite a region long torn by conflicts and divisions.

The NSR projects, which appeared to be at a standstill under the subsequent Trump presidency, might revive thanks to the emergence of a regional NATO ally, Turkey. With its Pan-Turkist strategy, Ankara could hinder China and the Silk Road Economic Belt (SREB) initiative by leveraging the Muslim community of Xinjiang, giving the U.S. NSR another chance for success (Turkey and pan-Turkism in Central Asia: challenges for Russia and China).

By implementing the NSR, Washington could undermine the China-Central Asia-West Asia Economic Corridor (CCAWAEC) and the SREB, China’s routes to the Middle East and Europe, damaging the activities of the Russian-led CSTO and EAEU.

Furthermore, using its soft power, as China and Russia, Washington established the American University of Central Asia in Bishkek.

According to various experts, another factor can undermine the U.S. strategy in Central Asia, favouring the Sino-Russian counterpart. Western liberal democracies, in return for their investments and cooperation, make demands in the field of human rights and the form of government in the country. Some U.S. campaigns in Eurasia have resulted in the overthrow of existing regimes as their final effect.

Instead, for the leadership of China and Russia, what counts is the stability and security that the partner country can guarantee and the solidity of the alliance. They are hardly interested in democratic processes as a conditio sine qua non for their investments.

Since 2013, China has focused on Central Asian republics through the China-Central Asia-West Asia Economic Corridor, investing in Central Asia, the Middle East and the Southern Caucasus.

Kazakhstan is involved in SREB’s New Eurasian Land Bridge Economic Corridor, linking China to Europe through Russia. The country has received significant Chinese investments and has agreed to merge the Chinese Belt and Road Initiative with its strategic Nurly Zhol (Light Path). In the last decades, they signed agreements for 33 billion dollars investments.

Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, and Uzbekistan are regional members of the Asian Infrastructure Investments Bank (AIIB). Furthermore, China has obtained a strategic military base in Tajikistan, gaining the possibility to monitor the Wakan corridor, exploited by terrorist groups to move armaments in Central Asia and the Xinjiang region (Chinese military base in Tajikistan: regional implications).

Regarding soft power, obtaining a job position in China-affiliated companies is easier knowing the Chinese language. As a result, the success of Chinese institutions in Central Asia has increased, and Beijing offers many scholarships. Moreover, as noticed with the Russian Odnoklassniki and Vkontakte, the Chinese WeChat is highly used.

Conclusions

The United States has always embraced Mahan’s Heartland theory, which identified the control of maritime space as the necessary condition for world hegemony. The struggle to curb Chinese expansionism has shifted to the Indo-Pacific, partly underestimating a scenario as important as Central Asia (Geostrategy and military competition in the Pacific). The collapse of the Soviet Union had offered a window of opportunity not fully exploited.

China, Russia, and Iran, the three regional antagonists of the United States, welcomed the withdrawal of U.S. troops from Afghanistan as a victory. Iran has repeatedly stressed that, in accordance with Russia, the Islamic Republic of Iran does not tolerate interference by international actors in regional issues. Tehran believes that U.S. policies and its military involvement in countries like Afghanistan and Iraq are one of the leading causes of the region’s destabilisation, addressing them as ‘invasion’.

Notably, many countries, also in Central Asia, considered the withdrawal of U.S. troops from Afghanistan as a sign of Washington’s unreliability as an ally (The new geopolitical game of Afghanistan).

On the other hand, it must be considered that, although there are no official statements on the matter, the withdrawal may not simply be a shift of U.S. interests towards the Indo-Pacific, but rather be a new strategy aimed at undermining the Chinese, Russian and Iranian interests in the area.

The collapse of the Ghani government and the consequent seizure of power by the Taliban with a chain reaction that could destabilise the area from the Middle East to Central Asia, with a return of terrorism to Russia and the gates of Europe were easily predictable results from the advanced U.S. intelligence apparatus. Based on these considerations, it can be assumed that the U.S. strategy is based precisely on these eventualities. Leaving a destabilised region to key players, such as China, Russia and Iran, will force them to make a military effort to resolve the Afghan crisis and secure their borders. Moreover, it will expose them to the risk of enormous losses since their economic strategies, particularly Beijing’s BRI, have hugely invested in trade corridors that cross the region. Therefore, the U.S. strategy could obtain the maximum result, stopping the rise of China, Russia, and Iran, leaving them to solve the problems caused by the Afghan crisis and its consequences with minimum effort.

To enhance its presence, Washington might exploit the weaknesses of the Chinese strategy.

China has invested heavily in the region’s development through projects such as the BRI, causing some countries to fall into debt. This is the case of Tajikistan, Kyrgyzstan, and Turkmenistan. In addition, there is the issue of Uighurs in Xinjiang, who share faith, ethnicity, and culture with part of the Central Asian population. While their persecution had already raised antipathies towards the Chinese presence in Central Asia, further discontent arose from the fact that Chinese investments create jobs for their workers without promoting local employment. Protests broke out in both Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan. The United States could exploit local discontent by promoting its investments as an alternative to Chinese ones.

Russia does not have the capital to rival China’s economic expansion. Moscow’s efforts are to ensure security on its blizhnee zarubezhe (near abroad) and lebensraum (vital space), where the Kremlin aims to strengthen its military and economic presence and political influence.

Russia perceives NATO’s action as an attempt to encircle the Russian Federation by exploiting the southern and western border, the least defensible from a geographical point of view, to keep the Kremlin in check. For this reason, recently, the Russian Foreign Minister, Sergey Lavrov, called Afghanistan neighbouring countries and central Asia to not host U.S. or NATO military forces following their withdrawal from Afghanistan.

India and European countries might facilitate the U.S. presence in the region and possibly enlarge NATO military presence in the future. Investments in crucial infrastructure, as the Trans-Caspian pipeline, might push Central Asian countries to forge alliances with the Western world.

Interconnectivity and a balance of regional and international powers might stabilise Eurasia and prevent the spread of terrorism.