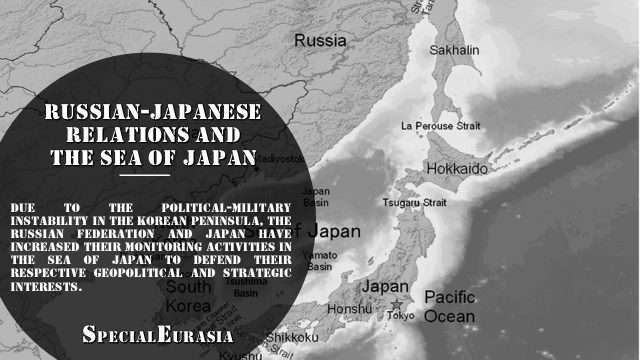

Russian-Japanese relations and the Sea of Japan

Geopolitical Report ISSN 2785-2598 Volume 17 Issue 5

Author: Riccardo Rossi

Due to the political-military instability in the Korean Peninsula, Moscow and Tokyo have increased their monitoring activities in the Sea of Japan to defend their respective geopolitical and strategic interests.

Over the past few years, the Sea of Japan’s increased political-military instability in the Korean Peninsula, primarily due to the development of new nuclear programs promoted by Pyongyang, has led the Russian Federation and the Japanese government of Shinzō Abe (2012-2020) to screen this geo-maritime space as a strategically vital area for the defence of their respective interests.[1]

The objective of the analysis will be to identify the geopolitical foundations that lead Moscow and Tokyo to consider the Sea of Japan a space of high strategic interest, deepening how these judgments affect the definition of their geostrategic choices.

The Sea of Japan in the Russian and Japanese geostrategic visions

In order to understand the geostrategic importance attributed by the Russian Federation and the Rising Sun to the Sea of Japan, it is necessary as a first analytical step to evaluate the geophysical structure of this geo-maritime space, which can be summarised in two characteristic features. The first one can be asserted to its intermediate position between the northern coastal segment of the western Asia-Pacific area (including the Korean and Russian coastline) and the Japanese archipelago. The second peculiar element of the Sea of Japan is referable to the structure of the semi-closed sea since four maritime straits delimit it: Tartars, La Pérouse, Tsugaru and Korea that connect to the maritime areas adjacent to it. Of these straits, the Tartar one (subject to the sovereignty of Moscow) together with La Pérouse (separates the Japanese territory from the Russian archipelago of Kurili, partly claimed by Tokyo),[2] interconnect the Sea of Japan with the adjacent maritime space of Okhotsk. The Tsugaru Narrowing connects the Sea of Japan with the Pacific Ocean. Finally, the Korea Channel connects this maritime space with the East China Sea.

For Tokyo and Moscow, this conformation of the Sea of Japan constitutes a highly influential factor in defining their respective geopolitical priorities in this geo-maritime area.

In the case of the Russian Federation during the second (2012-2018) and the current third (2018-in-office) Presidential term, Vladimir Putin has progressively increased his attentions towards the territories near the Sea of Japan to respond to three main concerns:

- The growing geopolitical instability of the Korean Peninsula due to Pyongyang’s nuclear missile programs and the corresponding increase of the U.S. presence in support of Seoul.[3]

- The decision of President Barack Obama (2009-2017), confirmed by the subsequent Trump (2017-2021) and Biden (2017-in office) administrations, in implementing a specific U.S. foreign policy project for the Asia-Pacific region called Pivot to Asia, aimed at containing the political-military rise of the People’s Republic of China (PRC) within the First Island Chain.[4]

- The proximity of the Japanese archipelago and the related U.S. bases to its segment of the Asian coastline and the main sea straits of La Pérouse, Tsugaru and Korea as a danger to the safety of coastal cities and the free navigation of its vessels in the Sea of Japan through the restrictions mentioned above.

This last concern of the Kremlin is linked to the hypothesis that the United States could use their military outposts in the Rising Sun as a launching point for power projection operations against the Russian military installations located along their coastline and for missions aimed at imposing their sea control near Korea, La Pérouse and Tsugaru straits, thus reducing the manoeuvring capabilities of the Russian Pacific Fleet.[5]

In this context, the Russian Federation has strengthened its military presence in the Sea of Japan by adopting a plan that combines the optimisation of military bases with regular training activity.

Regarding the enhancement of military outposts, it is necessary to recall the tactical-strategic importance recognised by the Kremlin to the Ukrainka air force outpost (home of Tu-95 strategic bombers) and the two Pacific Fleet headquarters: Vladivostok and Petropavlovsk-Kamchatskiy. The latter hosts the new Borei Class SSBN and Yasen Class SSGN submarines. In addition to the Pacific Fleet and Ukrainka base, the Eastern Military District’s Forces should be mentioned, which acquired the Iskander, S-300/400 missile systems and Su-35 jets.[6]

Referring to the training activities, since 2010, Moscow has been organising regular exercises in the Sea of Japan, including the Vostok manoeuvre, which in the 2018 edition involved:

«297 thousand troops, 1,000 aircraft, 80 ships, 36 thousand tanks, also seeing the participation of an aliquot of the military of the People’s Republic of China».[7]

This militarisation operation of the Japanese Sea implemented by Moscow has increased tensions with Tokyo, leading the Shinzō Abe government (2012-2020) to consider the Russian foreign policy a potential threat to Japanese economic and strategic interests.[8]

Regarding Tokyo’s economic interests, the Sea of Japan represents a virtual geo-maritime space due to the sea lines of communications (SLOC) that, passing through the narrowings of Korea and Tsugaru, interconnect some of its marine LNG terminal(s)[9] with the most important trade routes of the Asia-Pacific region such as Malacca, the Aleutians, the North Sea Route (NSR), San Diego and Panama.[10] From this type of economic attention, the Japanese government has partly derived the strategic value of the Sea of Japan, linked to the high level of geopolitical instability of the Korean peninsula, the Russian military presence in particular of the Pacific Fleet and the increasing assertiveness of the People’s Republic of China in the East China Sea. In this regard, the Rising Sun has developed a political-military doctrine that combines a partial redefinition of the pacifist constitution through the amendment of Article 9,[11] increased spending for the Japan Self-Defense Force (JSDF) and participation in manoeuvres that the Pentagon has organised in the Sea of Japan and the East China Sea.

Regarding funding to the JSDF, much of it is to support the Air Force (JASDF) and Navy (JMSDF).

In the case of the JASDF, the Shinzō Abe government has set out to acquire new F-35, P-8, E-2C Hawkeye aircraft and redefine the air force command and control system by establishing three main defence zones: northern, central and western. [12]

About the investment plan for the JMSDF, Tokyo has foreseen the design of a new surface and submarine vessel. In the first case, it is necessary to mention the construction of the Helicopter Destroyers or DDH (Izumo class), initially used as a ship for the transport of helicopters, but with the necessary modifications, it could host the F-35 B version. Regarding the submarine flotilla, Tokyo has developed conventional propulsion boats (SSK) called Soryu class, deployed between the bases of Kure, Yokosuka and Kobe.[13]

Concurrently with the rearmament program, Tokyo has fostered cooperation with the U.S. Navy Seventh Fleet at Yokosuka and the Amphibious Ready Group (ARG) device based at Sasebo.[14]

Overall, this participation of the Shinzō Abe government in the military manoeuvres organised by the Pentagon has a twofold objective. On the one hand, to improve the readiness and interoperability with the U.S. armed forces. On the other hand, maintain localised sea control in the main straits of the Sea of Japan: Korea, La Pérouse and Tsugaru. This last purpose responds to the geostrategic need to govern the Sea Lines of Communications, which cross this geo-maritime space and the ECS interconnecting the port network of the Rising Sun with the main sea routes of the Asia-Pacific region.[15]

Conclusions

From what is discussed in the analysis, it is clear that the Sea of Japan constitutes for the Russian Federation and the Rising Sun a geo-maritime space of high political-strategic value. Indeed, both countries recognise the high geopolitical instability of the Korean Peninsula, whose effects could negatively affect the geopolitical balances of the Japanese Sea. Notwithstanding this element of common geopolitical evaluation, Moscow and Tokyo identify different political-strategic objectives for this geo-maritime space.

Moscow’s aims are mainly strategic-military, focusing in particular on the role of the Pacific Fleet, the Ukrainka airbase and the Eastern Military District’s Forces in guaranteeing the security of the Russian coastal territory both from possible U.S. power projection operations and from the will of Washington and Tokyo to establish their sea control in the straits of Korea, La Pérouse and Tsugaru.

With the 2013 publication by the Shinzō Abe government of the National Security Strategy, the Rising Sun identified the Sea of Japan as a vital space for the protection of its national interests in the economic and strategic spheres. Tokyo sees the centrality of this geo-maritime space for the functioning of its economic system in the face of the Sea Lines of Communications (SLOC), which passes through the narrows of Korea, La Pérouse and Tsugaru interconnect some of the maritime LNG terminal(s) with the most crucial maritime communication routes crossing the Asia-Pacific region.[16]

In the strategic sphere, the Shinzō Abe administration notes that the Korean peninsula’s instability, the military manoeuvres of the Russian Pacific Fleet, and the growing assertiveness of Beijing in the ECS constitute potential danger factors for Japanese national security. From these two evaluations, Tokyo identifies the necessity to increase its military expenses and, at the same time, to participate in the exercises organised by the Pentagon in the ECS.

Overall, the attribution by Moscow and Beijing of a geostrategic centrality of the Japanese Sea to protect their interests has led to a progressive phenomenon of militarisation of this geo-maritime space, causing an increase in geopolitical instability.

Sources

[1] Sacko. D, Winkley. M, All Quiet on the Eastern Front? Japan and Russia’s Territorial Dispute, Journal of Indo-Pacific Affairs, 2020.

[2] Rossi R (2021) The geostrategic role of the Kuril Islands in the Russian foreign policy for the Asia-Pacific Northwest area, Geopolitical Report, Vol. 14(4), SpecialEurasia. Retrieved from: https://www.specialeurasia.com/2021/12/14/geostratey-kuril-islands-russia/

[3] Rozman. G, Joint U.S.- Korea academic studies The east Asian whirlpool: Kim Jong-Un’s diplomatic shake-up, China’s sharp power, and trump’s trade wars, Korea Economic Institute of America, 2019

[4] Amighini. A, China Dream: Still Coming True?, Edizioni Epoké – ISPI, Novi Ligure, 2016.

[5] Japan Ministry of Defense (2021) Development of Russian Armed Forces in the Vicinity of Japan. Link: https://www.mod.go.jp/en/d_act/sec_env/pdf/ru_d-act_e_210421.pdf

[6]Sacko. D, Winkley. M, All Quiet on the Eastern Front? Japan and Russia’s Territorial Dispute, Journal of Indo-Pacific Affairs, 2020, p.17

[7] Japan Ministry of Defense (2021) Development of Russian Armed Forces in the Vicinity of Japan. Link: https://www.mod.go.jp/en/d_act/sec_env/pdf/ru_d-act_e_210421.pdf , p.4

[8] Burke. E, Heath. T, Hornung. J, Logan Ma, Lyle J. Morris, Michael S. Chase, China’s Military Activities in the East China Sea Implications for Japan’s Air Self-Defense Force, RAND Corporation, Santa Monica, Calif,

[9] CIA The World Factbook, Japan. Link: https://www.cia.gov/the-world-factbook/countries/japan/#economy

[10] Limes Rivista Italiana di Geopolitica, Gedi, Rome, issue 7/2019

[11] Costituzione dell’Impero del Giappone (1946). Link: https://www.art3.it/Costituzioni/costituzionegiappone.pdf

[12] Burke. E, Heath. T, Hornung. J, Logan Ma, Lyle J. Morris, Michael S. Chase, China’s Military Activities in the East China Sea Implications for Japan’s Air Self-Defense Force, RAND Corporation, Santa Monica, Calif., p.16

[13] Ibid

[14] Ibid

[15] Limes Rivista Italiana di Geopolitica, Gedi, Rome, issue 7/2019

[16] Ibid