The geostrategic role of the Kuril Islands in the Russian foreign policy for the Asia-Pacific Northwest area

Geopolitical Report 2785-2598 Volume 14 Issue 4

Author: Riccardo Rossi

For the Russian Federation, since its conquest against the Japanese Empire at the end of World War II, the Kuril Islands have represented an island area of vital geostrategic importance for the defence of its interests in the Asia-Pacific Northwest.

In the last decade of the 21st century, following the affirmation of the Asia-Pacific region as the primary and future theatre of geopolitical competition between the People’s Republic of China (PRC) and the United States,[1] the Russian Federation has found itself in the position of increasing the political-strategic level of vigilance in defence of its territories in this area, paying particular attention to the geo-maritime space near Vladivostok, Petropavlovsk-Kamchatskiy and the Kuril archipelago. If, on the one hand, this decision by Moscow can be considered a logical response to the increase in geopolitical instability in the Asia-Pacific region, on the other, it has generated concern in the governments of countries close to their territories, such as Japan and South Korea.

Given these considerations, the objective of this analysis is to understand the geostrategic reasons that lead Moscow to consider the Kuril archipelago an indispensable geo-maritime area for the defence of its interests in the Asia-Pacific Northwest area, in order to evaluate how these influence the definition and elaboration of military strategies.

The geostrategic importance of the Kuril Archipelago

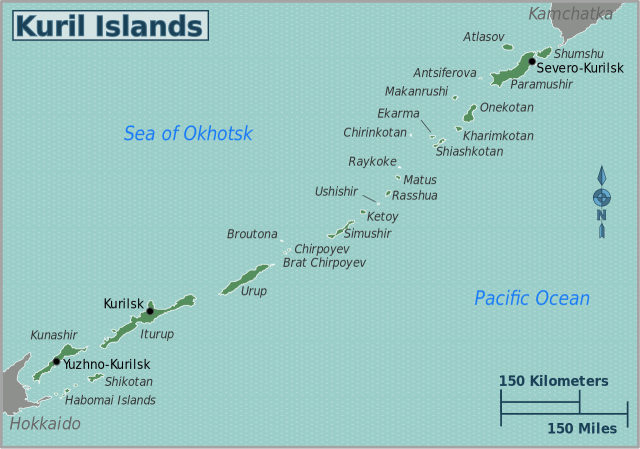

A first possible explanation of the geostrategic importance attributed by the Russian Federation to the archipelago of the Kurils (extending for 1200 km from the southern tip of the Russian peninsula of Kamchatka to the north-eastern coast of the Japanese prefecture of Hokkaido) is attributable both to its intermediate position between the island of Sakhalin and the open Pacific and to its proximity to the Strait of La Pérouse, which separates Sakhalin to the north from the Japanese prefecture of Hokkaido to the south, connecting the Japanese Sea with the Okhotsk maritime space.

For the Russian Federation, this particular arrangement of the Kuril Islands, as it had been previously for the Tsarist Empire and the Soviet Union (USSR), represents an indispensable space for the defence of its eastern borders.

This assertion is partly confirmed by considering the conflicting Russian-Japanese relations for the control of the Kurils and Sakhalin Island between the late 1800s and the conclusion of World War II, which sanctioned Soviet dominance of this geo-maritime area, although not validated in the 1951 San Francisco Peace Treaty. The effects of this non-recognition led the USSR delegates not to ratify the document, and at the same time pushed the Japanese governments that followed from 1951 until the Shinzō Abe administration (2012-2020) to ask Moscow several times for the restitution of the four southern islands of the Kuril archipelago (Habomai, Shikotan, Kunashir and Iturup), because they were part of Japanese territory until the invasion of the Red Army in August 1945.[2]

With the beginning of the Cold War, the Soviet Union did not endorse the Japanese request because the archipelago, due to its geographical position, constituted an indispensable asset for Moscow in responding to two political-strategic priorities identified for the Asia-Pacific Northwest area.

The first one concerned the need to protect their Pacific territories from possible U.S. military operations launched from their bases located in the Japanese archipelago and near the island of Guam. The second preeminence specified the need to control the Kuril Islands since this chain of islands represented the only access and exit route from the Sea of Okhotsk to the open Pacific.

The pursuit of these two political-strategic priorities led the Soviet Union to develop a military doctrine for the Asia-Pacific Northwest area, which, as reported by Major-General G. Mekhov, in the text Military Aspects of the Territorial Problem, recognised the Kuril Archipelago: «[…] substantial importance in military-strategic planning, as a natural barrier on the approaches to the Sea of Okhotsk and Maritime Province.» [3]

Since 1970, this assessment is reflected in the Soviet government’s decision to militarise the Kurils in order to impose its sea control in the waters of the Sea of Okhotsk as it had become home to the Pacific Fleet’s Delta-I and III class ballistic missile nuclear submarines (SSBNs) stationed at the port city of Petropavlovsk-Kamchatskiy, located at the southern tip of the Kamchatka Peninsula.[4]

With the dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1991 and the birth of the Russian Federation, the first two presidencies of the newborn state, Boris Nikolaevič El’cin (1991-1999) and Vladimir Putin (2000-2008) adopted a policy of reducing Moscow’s presence in the north-western Asia-Pacific area, concentrating its attention on the Kola peninsula and the Caucasus, thus reducing the military assets deployed in the Kuril archipelago.

This idea mainly remained prevalent in Putin’s agenda until the election of Barack Obama (2009-2017) to the presidency of the United States and the subsequent identification of the geopolitical importance of the Asia-Pacific region for U.S. political-military interests. An evaluation that led Hillary Clinton in 2011 to present a specific foreign policy program for the Asia-Pacific called Pivot to Asia, confirmed by the successive Presidencies Trump and Biden, aimed at countering the growing expansion of the People’s Republic of China (PRC) within the geo-maritime space between the Chinese coastline and the first island chain.

This decision by the United States has provoked innumerable reactions from certain states in the region, including the Russian Federation. During his third (2012-2018) and fourth (2018-in-office) presidential terms, Vladimir Putin reconsidered the Soviet posture towards the Northwest Asia-Pacific area to address in cooperation with the People’s Republic of China (PRC) the growing U.S. political-military presence in the East China Sea, Japan, the Korean Peninsula and in the vicinity of the Kuril Archipelago and the Strait of La Pérouse.

Among these territories, it is worth remembering the particular geopolitical importance attributed by the Russian Federation to Korea by virtue of sharing with the North Korean State a 22-kilometre segment of the border, but at the same time for the proximity of the city of Vladivostok, headquarters of the Pacific Fleet, to this demarcation line. Hence Moscow’s growing worries about the increase in political and military instability between North and South Korea, primarily due to Pyongyang’s nuclear tests and the constant U.S. pressure against Kim Jong-un’s dictatorship.

The precarious stability of the Korean peninsula, together with the increased assertiveness of the United States in the other areas mentioned above, has led the Putin presidency to elaborate a military strategy that combines two lines of action. The first involves modernising military assets located in the two main bases of the Pacific Fleet, such as Vladivostok and Petropavlovsk-Kamchatskiy and the Kuril archipelago. An example of this is the deployment of the new SSBN Borey at Petropavlovsk-Kamchatskiy and the decision to allocate funding for the rearmament of the Kuril Archipelago.[5]

The second line of intervention thought by Moscow, as summarised in the Russian maritime doctrine of 2015, presumes the development of a military partnership with the People’s Republic of China (PRC) in order to maintain control of the geo-maritime space adjacent to the Korean peninsula and near the Strait of La Pérouse. In this case, the Russian Federation, since 2010, has organised regular exercises as happened with the Vostok 2018 conducted in September in which China took part with 3200 militaries.[6]

Conclusions

With the election of Obama to the presidency of the United States and the consequent affirmation of the policy of Pivot to Asia, the Putin presidency has reconsidered the geostrategic importance of the Kuril Archipelago as an indispensable geo-maritime area for the protection of its interests in the north-west Asia-Pacific area, mainly ascribable to the containment of the American presence in the East China Sea, in Japan, in the Korean peninsula and the Strait of La Pérouse.

This re-evaluation of the Kuril Archipelago can be seen in the adoption of a programme aimed at the deployment of missile and maritime defence systems there and at providing the Vladivostok-based Pacific Fleet with new weapon systems has been the case since 2013 with the deployment of SSBN Borey at Petropavlovsk-Kamchatskiy.[7]

Having identified this complex geostrategic framework, it is possible to hypothesise that in the years to come, the Kuril Archipelago will be an important area for the Russian Federation for the implementation of three types of operations, such as:

- Acting as a bridgehead between the submarine base of Petropavlovsk-Kamchatskiy and the headquarters of the Pacific Fleet located in Vladivostok.

- To increase the level of political-military pressure towards the Strait of Pérouse and the U.S. bases located in Japan, such as Yokosuka (headquarters of the Seventh Fleet) and Sasebo (home to the second U.S. Navy base, where the Amphibious Ready Group (ARG)is stationed).[8]

- To maintain a situation of geostrategic stability in the Korean peninsula through the political-military support of the People’s Republic of China.

The pursuit of these three operations, being in good part connected to the tactical-strategic enhancement of the Kuril archipelago, it is possible to affirm with a certain margin of security that, in the following years, the Russian Federation will not cede to Japan the four islands (Habomai, Shikotan, Kunashir and Iturup) claimed by the Rising Sun for 70 years.

Source

[1] Rossi, Riccardo (2021) Geostrategy and military competition in the Pacific, Geopolitical Report Vol.10(1), SpecialEurasia. Retrieved from: https://www.specialeurasia.com/2021/08/06/geostrategy-pacific-competition/ (accessed 14/12/2021)

[2] Kuroiwa. Y, Russo-Japanese territorial dispute from the border regional perspective, UNISCI Discussion Papers, núm. 32, mayo, 2013, pp. 187-204 Universidad Complutense de Madrid

[3] Major-General G, Mekhov, Military Aspects of the Territorial Problem Krasnaya Zvezda, 22 July 1992, p.3.

[4] Hara. K, Ikegami. M, New Initiatives for Solving the Northern Territories Issue between Japan and Russia: An Inspiration from the Åland Islands, Issues & Insights Vol. 7- No. 4, April 2007, pp. 57-58

[5]Japan Ministry of Defense, Development of Russian Armed Forces in the Vicinity of Japan,03/2021

[6] Rozman. G, Joint U.S-Korea Academic Studies, 2019

[7] Rumer. E, Sokolsky. R, Vladicic. A, Russia in the Asia-Pacific: Less Than Meets the Eye, Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, 2020

[8] Kiley.G, Szechenyi. N, U.S. Force Posture Strategy in the Asia Pacific Region: An Independent Assessment, Center for Strategic and International Studies, Washington, DC, 2012, p.73