Geopolitical Report ISSN 2785-2598 Volume 37 Issue 3

Author: Silvia Boltuc

Amidst escalating concerns over the Sahel’s increasing jihadist activities and destabilisation processes that have intricately impacted regional geopolitical dynamics, this report aims to delve into the current state of affairs in the Sahel region, with a focused examination of jihadist groups and internal political and security dynamics, given the pivotal role the region plays in shaping Africa’s geopolitical landscape.

The Sahel region: Background Information

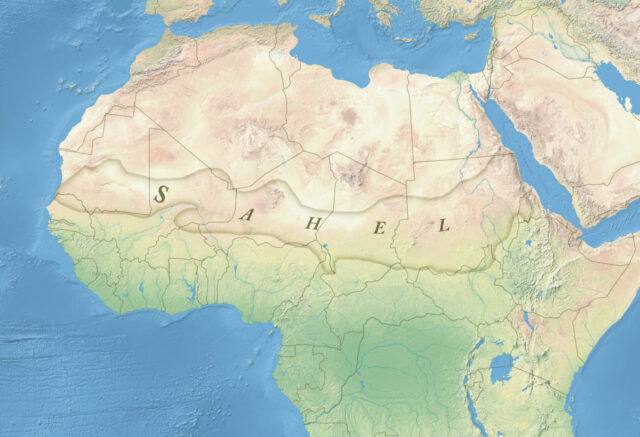

The word “Sahel” originates from the Arabic word ساحل (sāḥil) and translates to “shore” or “border.” In the geographical context, it refers to the transitional zone or strip of land between the Sahara Desert to the north and the more fertile savanna or grasslands to the south in Africa. The Sahel region spans 5,900 km from the Atlantic Ocean in the west to the Red Sea in the east.

This area has increasingly become a hotbed of escalating violence and instability, largely under the control of military forces and jihadist groups. This situation poses a risk of spreading turmoil to other parts of Africa.

Over the past decade, Europe has invested 600 million euros in civil and military missions in the Sahel with poor results. The security situation in the region remains highly critical, coupled with notably low levels of human development. Jihadist groups have gained strength, exploiting weaknesses within national institutions.

The region has faced a spate of coups in countries like Mali, Chad, Burkina Faso, Sudan and Niger, leading to a diplomatic crisis in Europe. This crisis has prompted closer ties between Sahel’s countries and Russia, especially thanks to the activities of the private military company (PMC) the Wagner Group.

The region’s relationships have worsened not just with Europe but also with the longstanding French influence. France’s perceived failure to hand over authority to Fama, the Malian army, after its intervention alongside the Bamako government in the 2012 Operation Serval, has further deepened fractures.

In early December, Niger and Burkina Faso followed Mali’s lead by announcing their withdrawal from the EU-funded G5 Sahel joint force, initially established in 2014 to enhance counterterrorism coordination. This decision echoes Mali’s action from the previous year. With the expulsion of the French ambassador and the imminent withdrawal of French military forces by the early weeks of 2024, along with the rejection of two European Union missions for security and defence (EUCAP Sahel Niger and EUMPM), Niger’s actions further underscore the declining influence of France and Europe in the region.

Many of the regional populations perceive that democracy has failed to deliver on its promises. However, it’s important to note that the democracies in the Sahel region were in their early stages and were incomplete, marked by significant corruption. All services entailed a financial charge, ranging from university examinations to hospital admissions, and extend to bribes required at each checkpoint. Corruption in the Sahel is an institutionalised way of managing people and exercising power in situations of limited accountability. These constant payments are viewed as an ongoing humiliation of the civilian population by the authorities, leading to increased disillusionment with democracy.

The elections in Niger, although praised as a success by the West, have been another example of corruption, as significant irregularities marred them.

Understanding the Escalating Spiral of Violence in the Sahel: Exposing the Root Causes

The Sahel region stands as one of the world’s most impoverished areas, evaluated based on various indicators, including human development, per capita income, literacy rates, and life expectancy. Countries within this geographical expanse experience remarkably high population growth, exemplified by Mali and Niger, where populations double every 30 years, averaging around 7 children per capita.

This demographic surge inevitably strains the labour market’s capacity to absorb such numbers, further compounded by economic stagnation in these landlocked nations. Moreover, the Sahel area grapples with unprecedented levels of violence, fuelling a rapid increase in the number of displaced people, creating an unparalleled humanitarian crisis globally.

One of the primary causes of the jihadist group’s success is the widespread desire for protection among local populations within an environment of extreme violence and the failure of democratic processes.

Still, the triggers for the current spiral of violence in the Sahel originated also from external contexts, including:

- The Algerian Civil War, also known as the “black decade,” which marked a severe disruption of the electoral path in the early ‘90s.

In 1992, a coup d’état transpired in Algeria amidst various socio-political-economic issues, including the collapse of oil prices in 1986, a burgeoning jobless population, and widespread corruption within the government. The ruling National Liberation Front (FLN) banned all opposition.

The Islamic Salvation Front (FIS) was established in 1989 under the influence of the Muslim Brotherhood. Concerned by the FIS’s initial victory in the 1991 elections, the Algerian army intervened, nullifying the electoral process of forestalling the establishment of an Islamic state. This intervention led to the dismantling of the FIS, with surviving members radicalising and fleeing to northern Mali.

These individuals integrated into Mali through policies like mixed marriages and received tacit acceptance from Malian authorities, seen as a counterweight to the Tuareg ethnic groups in the capital region.

- Another pivotal event affecting the Sahel region was the Libyan crisis, part of the broader Arab Spring movements. During this tumultuous time, Western support for protests against Muammar Gaddafi’s regime resulted in his overthrow.

Gaddafi’s demise led to chaos and the dispersion of sophisticated weaponry from Libya. Within Gaddafi’s militias were Sahelian citizens who had found work in Libya; following his death, these individuals returned to Mali with advanced weaponry, upsetting the balance of power between rebels and the government in Mali. This influx of weaponry intensified the conflicts within the region, exacerbating an already dire situation in the Sahel.

The ongoing spiral of violence in Mali involves three primary components: the jihadist element, the irredentist faction represented by the Tuareg, and the dynamics associated with arms trafficking. The crisis, which began in the northern part of the country, is rapidly spreading across the region. Such escalation might lead to potential consequences affecting Ghana, Togo, Ivory Coast, and other neighbouring areas.

Currently, the destabilisation is predominantly driven by jihadists aspiring to establish a caliphate and enforce Shari’a, the Islamic law. The Tuareg irredentists have been sidelined and occasionally assimilated into jihadist factions.

The Islamist groups present in the area refer to al-Qaeda (Jama’at Nusrat al-Islam wa al-Muslimeen – JNIM. Part of this group of fighters emigrated from Algeria) and to the Islamic State (also known in the region as Daesh).

Some of these groups linked to the Islamic State are a metamorphosis of listed terrorist organisation Boko Haram, formally named Jama’atu Ahlis Sunna Lidda’awati Wal-Jihad. In March 2015, Boko Haram leader Abubakar Shekau’s pledge of allegiance to Islamic State was accepted, and the group began operations under the name ISWAP – Islamic State West Africa Province. The second group is the Islamic State’s Sahel Province (ISSP), which has spread its governance efforts in northeastern Mali and expanded governance and military activity closer to the Nigerien capital in recent months.

There is a cluster around Lake Chad where the Islamic State operates and one at the intersection of Mali, Niger and Burkina Faso, where there is both the Islamic State and al-Qaeda, mainly the second.

Factors Driving the Ascendance of Jihadist Groups in the Sahel Region

Upon analysis, it can be deduced that poverty, religious and ideology issues are not the primary factors driving the rise of these fighters.

In the past, the Sahel region was known for its remarkable religious tolerance and peaceful coexistence, to the extent that even the most rigid Muslims criticised this acceptance of religious diversity. Currently, it’s the region witnessing the most rapid expansion of jihadist groups.

The primary driver behind these groups’ success in the region is the perception among local populations of the abuses inflicted by their governments’ security forces upon civilians. Many reports confirm that this violence prompts many civilians to sympathise with or join these groups. Government forces indiscriminately blame entire villages believed to be affiliated with jihadist groups, resulting in widespread punishments. Consequently, there’s an increasing demand for protection from the civilian population, which jihadist groups are fulfilling.

Looking at the statistics, the official security forces have caused more civilian casualties than jihadist and irredentist groups, accounting for over half of the total victims.

Contrary to common belief, pursuing wealth is not a primary motivator for people joining jihadist groups. In reality, apart from the elite members, these fighters live challenging lives, often concealed in desolate areas. Many do not receive regular salaries, but rather tangible items as payment. Consequently, significant funds are not required to finance the fighters’ activities.

Their followers tend to be very young, often minors. Any accumulated resources are used for survival and to afford dowries for marriage. They acquire weapons through theft, frequently targeting depots of the official security forces in their attacks. One of the funding methods worth noting is that these groups have realised the West is willing to pay substantial amounts in ransoms. Additionally, they engage in racketeering across various local businesses.

Conclusion

In the Sahel region, there’s a noticeable rise in militarism because of widespread insecurity, leading civilians to seek protection. This request is increasingly met by jihadist groups.

The government’s security forces also receive significant support as pursuing a military career is highly sought after, and almost every family has a member serving in the armed forces. Consequently, several coups have occurred amidst enthusiastic support from the public.

Sahel countries are undergoing a surge akin to European populism, a call for a decisive figure to restore the populace’s dignity. This manifests as a nationalistic form of populism aligning with particular ethnic groups, usually those located in the capital.

Consequently, a growing inclination towards sovereignty is observed. Some sections of the public don’t believe that the West failed to defeat jihadist groups, particularly in the first stage when they were particularly weak; instead, they suspect the West of allowing their presence to justify continued involvement in the Sahel, akin to a form of colonialism. The French government particularly faced these conspiracy theories, leading to the expulsion of its troops from Mali in 2022 and, following a coup, from Burkina Faso.

In Mali, the military transition continues to enjoy widespread popular support. Following the departure of French forces, Malian authorities sought assistance from the Wagner group.

Before the coup, they had requested Paris to bolster their presence with ammunition, military equipment, and troops on the ground as they faced threats from jihadist groups. However, France and the EU hesitated to align themselves with regional governments because of concerns about their antidemocratic tendencies, corruption, and human rights violations. This hesitation paved the way for increased Russian influence and the successful application of the ‘Syrian model’.

Wagner has been implicated in carrying out summary executions similar to those conducted by regular security forces, enhancing their effectiveness against jihadists. The group currently boasts a force of 1200 to 1500 men, a number that hasn’t diminished since the conflict in Ukraine began.

The UN was expelled after documenting these abuses, yet it functioned as an interposition force. Consequently, following its expulsion, the Bamako government sought Wagner’s support, enabling them to reclaim control in some areas from Tuareg insurgents. However, the Tuareg managed to evade confrontation and have dispersed into the desert. Presently, the Malian government is consolidating its presence in northern Mali, keeping a close watch on the dispersed rebels’ reactions.

In Niger, the ousted president had started crucial measures benefiting the population in the most remote regions. Potentially, the new political reality might lead to heightened discontent in those areas.

The Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) treaty mandates signatory nations to intervene in the event of a military coup, although such interventions have never occurred previously. Previous coups led to sanctions and diplomatic mediations.

Nigeria leads this coalition, given its population and GDP, that surpasses the combined total of other signatory states. The newly elected Nigerian president advocated for a military intervention in Niger, which faced opposition from the United States.

Presently, the coalition has imposed stringent sanctions, resulting in an unprecedented crisis in Niger. However, the government, in a display of spite towards the imposing nations, has barred the entry of essential humanitarian goods, exacerbating the crisis and causing initial dissent among the population.

In response, the junta has taken radical measures, severing security cooperation with Europe and forging agreements with Russia, possibly anticipating support from Wagner to counter potential unrest.

Furthermore, Niger’s military government abrogated the controversial Law 36-2015, which criminalised transportation of migrants north from Agadez to Libya and Algeria for onward transition to Europe, marking a significant diplomatic shift away from the Brussels.

In the forthcoming weeks, the EU is expected to respond. Brussels had previously set a red line for the democratically elected government, urging them to maintain migration control and refrain from making deals with Russia.

From a European perspective, there’s a need to contemplate the impact of Brussels’ policies in exacerbating militarism. Europe has notably redirected its aid more towards security and military aspects, for example, with military training mission such as EUTM, diminishing support for development initiatives.

Another important consideration pertains to the attraction of political Islam among the Sahel’s most dynamic population segments, particularly the younger generation. Government structures based on political Islam generally disapprove of armed guerrilla activities. This scenario raises the potential for local administrations to evolve into Islamic republics in the future.

Do you like SpecialEurasia reports and analyses? Has our groundbreaking research empowered you or your team? Now is your chance to be a part of our mission! Join us in advancing independent reporting and unlocking the secrets of Eurasia’s complex geopolitical landscape. Whether through a one-time contribution or a monthly/yearly donation, your support will fuel our relentless pursuit of knowledge and understanding. Together, let’s pave the way for a brighter future. DONATE NOW and secure your place in shaping the geopolitical narrative.